Xiang Zhang

East Meets West Where the West Begins

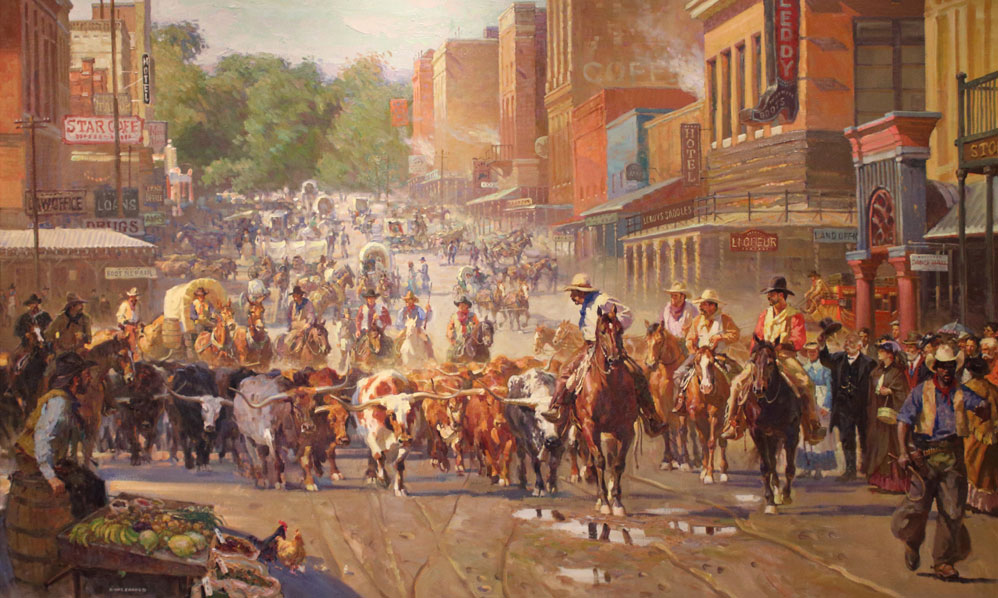

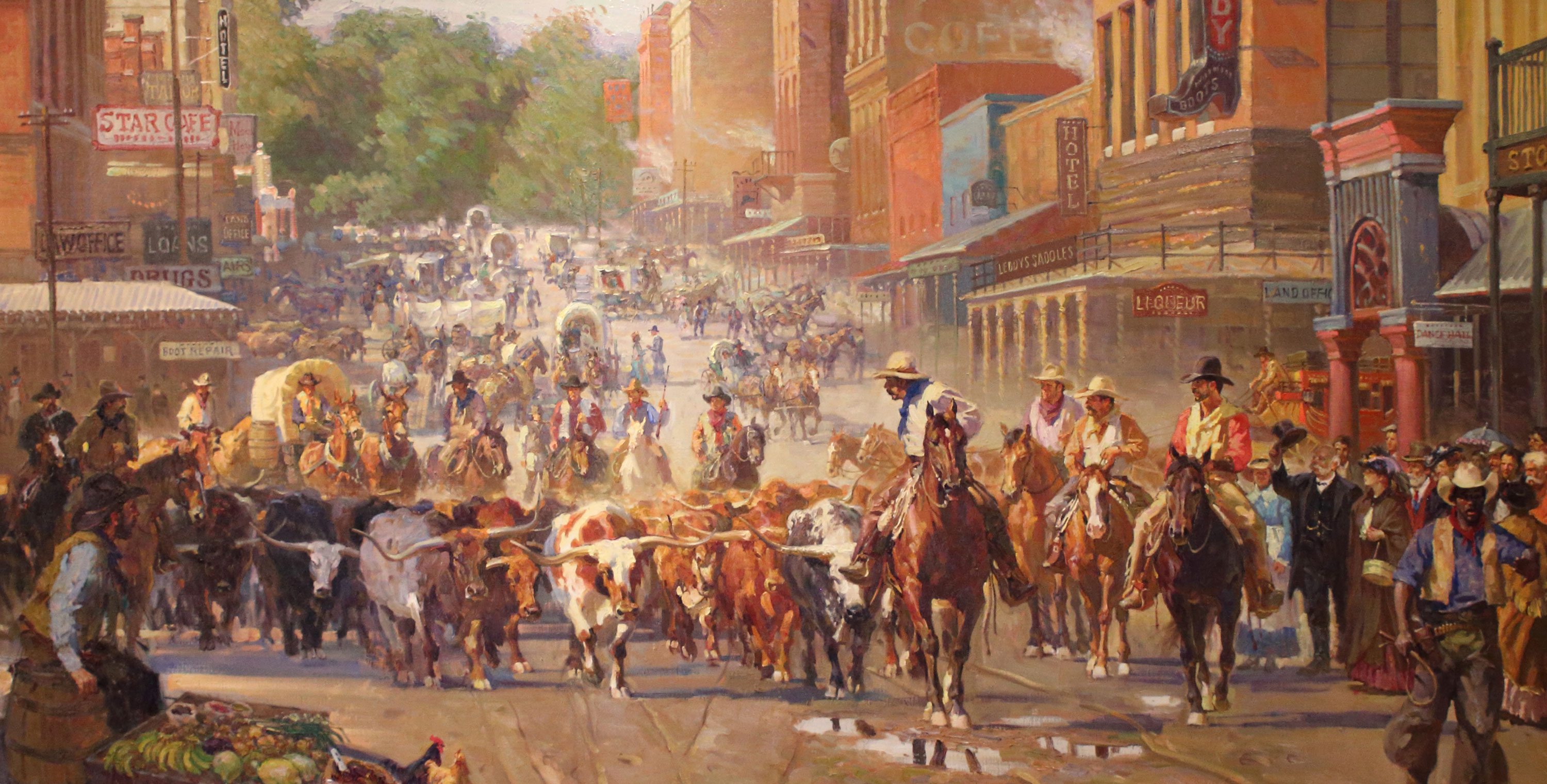

At an imposing 54 by 82 inches, “Arriving Fort Worth” is an incredible oil of an 1895 longhorn cattle drive sweeping into the world-famous Fort Worth Stockyards. The piece serves notice to bystanders that the cowboys have completed their epic journey from parts unknown to bring their product to market. They risked their lives and spent weeks on the trail to trade their herd for the highest price – such was Free Enterprise in the 19th century.

Winner - Best Western February / March by PlenAir Salon Art Competition

Hover over image

to view detail

Fort Worth has always embraced its Western heritage; now that he can paint anything he wants, Chinese-born artist Xiang Zhang embraces it too.

Zhang looks to working ranches and the real cowhands who work them, rodeos, rodeo parades, the Fort Worth Stockyards, livestock shows, museums, television Westerns and movies as inspiration for his powerful, detailed action scenes of the American West in the late 1800s.

Using his imagination and thousands of photographs he has taken to capture facial expressions and split seconds in time and motion, Zhang recreates iconic cattle drives and land rushes, Indian encounters, campfires, chuck wagon dinners, magnificent horses, longhorns and cowboys.

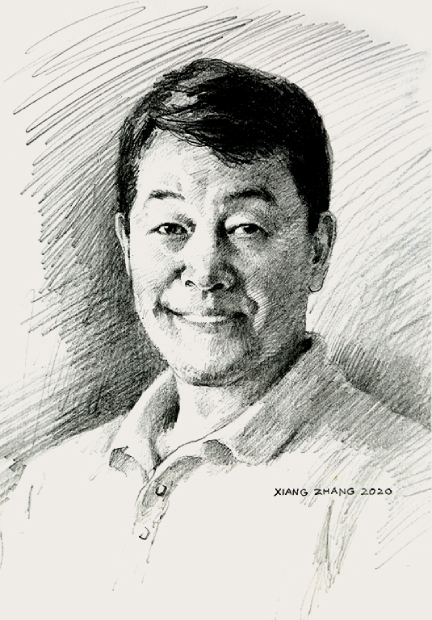

Xiang Zhang shoots reference photographs for his work

Click on the points below to learn more about Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China

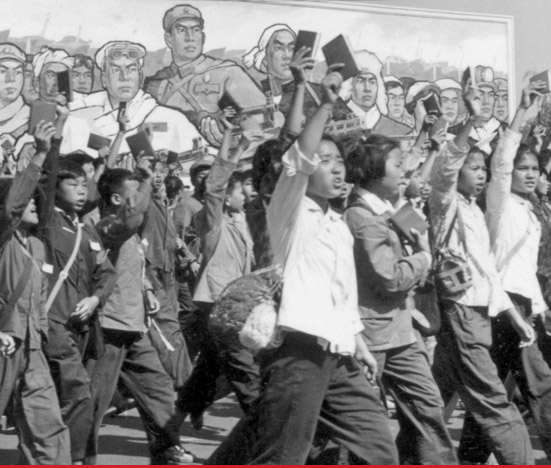

High school and college students known as the Red Guard wave copies of Chairman Mao Zedong's Little Red Book during a march in Beijing in 1966.

“You can paint anything you like here in America,” Zhang said. Artists from all over the world come here. When they come here, they want to stay here and realize their dreams. The Constitution protects everybody’s rights. You work hard, and you have opportunities.”

Zhang was 12 years old when Mao Zedong launched China’s devastating Cultural Revolution May 16, 1966.

Schools were closed. Zhang’s parents, who had been university professors, were sent out to work as farm laborers, and millions of people were tortured and imprisoned.

“Lots of people starved to death, many were tortured to death, some writers and artists suicided themselves,” Zhang recalled. “Mao inflicted mass horror, more of it on his own people than anyone else. The Cultural Revolution was just a disaster for China.”

But Zhang, who started drawing at the age of 6 and had an art tutor in elementary school, didn’t waste the free time.

“We had nothing to do, but I never stopped the study of art on my own. It was a passion,” he said.

“We had nothing to do, but I never stopped the study of art on my own. It was a passion.”

When a neighbor came back from Moscow University with art books filled with pictures of oil paintings, many of them by 19th century Russian masters, Zhang had no doubts about what he wanted to do with his life.

“From the time I was little, I had been making quick pencil sketches – mostly people’s faces and horses I saw in the fields while I was walking to school. I made a lot of them. My mother still has hundreds, probably thousands,” he said. “But the first time I saw an oil painting, it was just so beautiful and three-dimensional and full of color, I knew I had to paint with oil.”

The chaotic decade of the Cultural Revolution finally ended in 1976, and schools reopened. Zhang was among more than 5,000 young people who applied for 30 positions at the Central Academy of Drama in Beijing, where set design, play writing, directing, acting classes and his beloved oil painting, were taught.

The Central Academy of Drama in Beijing

“Zhang was among more than 5,000 young people who applied for 30 positions at the Central Academy of Drama in Beijing...”

“The entrance exam was very, very difficult. I was very lucky,” he said modestly.

Zhang completed four years of undergraduate work at the Academy and taught art history, art appreciation and drawing at the Beijing Broadcasting Institute while continuing to draw and paint.

“At that time in China the government would educate you for free, but they used you for what was best for them,” Zhang said. “During the Cultural Revolution, all painting was propaganda. Art was a tool for propaganda. I painted lots of Chairman Mao.”

Once doors to the Western World re-opened, the Chinese government sent Zhang’s father to the University of Pennsylvania as a visiting scholar to catch up on what had been happening in the free world. He returned to China and encouraged his son’s ambition to study in the United States.

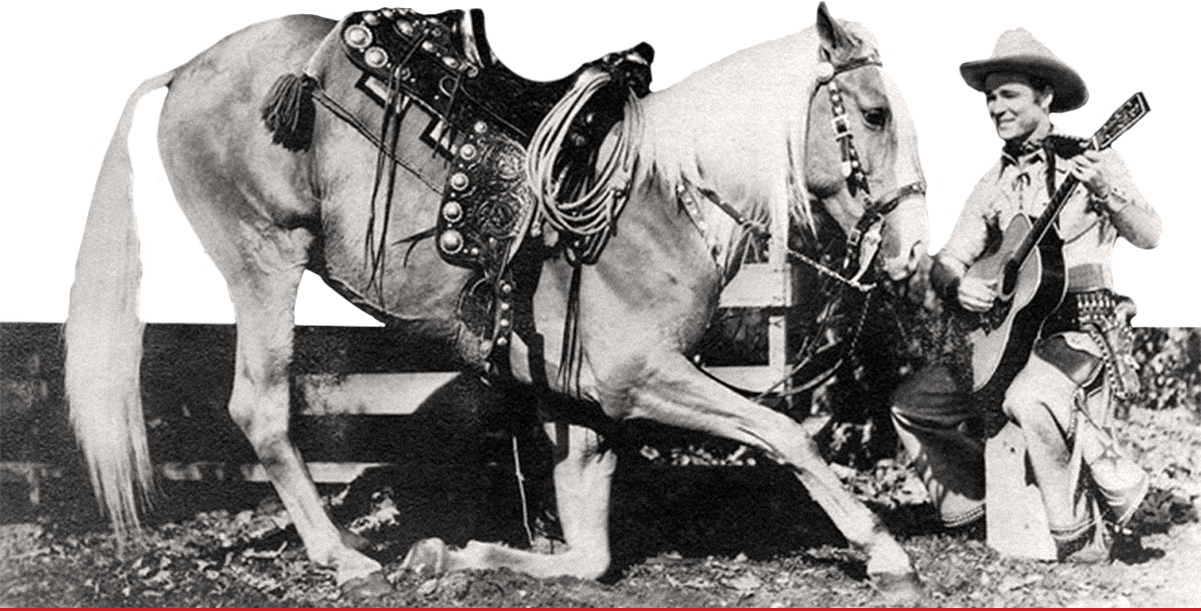

“My parents were scientists, but they loved art, and they encouraged me,” Zhang said. “I already knew this country was a great country for everything. I did lots of research before I ever came here. I read Hemingway and Tennessee Williams and Jack London and Arthur Miller, and we had watched old black and white Western movies when I was little. Cowboys just fascinated me.”

Famed Cowboy Roy Rogers and his horse Trigger

The wild freedom of the uncharted lands of the American West he saw on TV – and the opportunity to make his own way – drew Zhang to the United States. “I knew roughly what America was about, and I just loved it already, but I wanted to come and see what capitalism really is, and I stayed to see what I could do here.”

He earned a master’s degree in fine art from Tulane University, and, after graduation, worked designing sets and costumes for the New Orleans Opera House and elaborate floats for Mardi Gras parades, while continuing to paint and study on his own.

Encouraged by top awards in the first two art shows he entered, Zhang decided, “I can do this,” and turned his attention full time to fine art and his first love – cowboys and their horses.

“Horses have been part of Chinese history for about 5,000 years,” Zhang pointed out. “I am born in 1954, which was a ‘year of horse,’ considered a Chinese Zodiac animal. I started drawing horses in the Chinese style, in black ink on rice paper. I loved drawing them, and I have always loved to capture the expressions on people’s faces. Character and personality are reflected in faces.”

“Most of my paintings are full of action, and I can’t ask people to stop in the middle of what they are doing and ‘hold that pose’ for me. That is why I take so many photographs.”

A portrait of the artist, Xiang Zhang

Artists tend to excel at either finely drawn portraits or broad landscapes – sometimes with figures. Zhang, however, equally is adept at both. While widely known for his expansive landscape canvases, he also is a master at capturing the unique character of a subject in his portraits.

Zhang often takes 300 or so snapshots of a single subject in order to find the perfect expression so that he can make a pencil sketch of whom the person really is. The sketches on Western’s website are Zhang’s work.

The Chinese-born artist who was inspired by old Westerns and Russian painters is not much different than those cowboys of yesteryear. Zhang has made his own epic journey and now trades his weeks and months of labor to eager buyers – such is Free Enterprise in the 21st century.

And, he is still impressed by the fact that in America, you can paint and sketch anything you want.